No Sleep in a Flat Place

Article by Lexi McCloud

The mountains that come up all around this dirt road are my cradle. Born in Vermont, I immediately laid in her comforting bed, rocked to sleep by the slow, seasonal turn of the land. All my life, good and bad, happened between these hills. This cradle raised me in a way no human Mother or Father could. My true parentage may be the land itself. If you took the exact household of my childhood, and by the hand of God, dropped us in a city rather than Riverton, I don’t believe I’d have come out the same person at all. Many generations came before me; they lived and died on this soil, connecting me to it in ways I cannot explain or understand but that I feel, nonetheless.

I can’t sleep in a flat place.

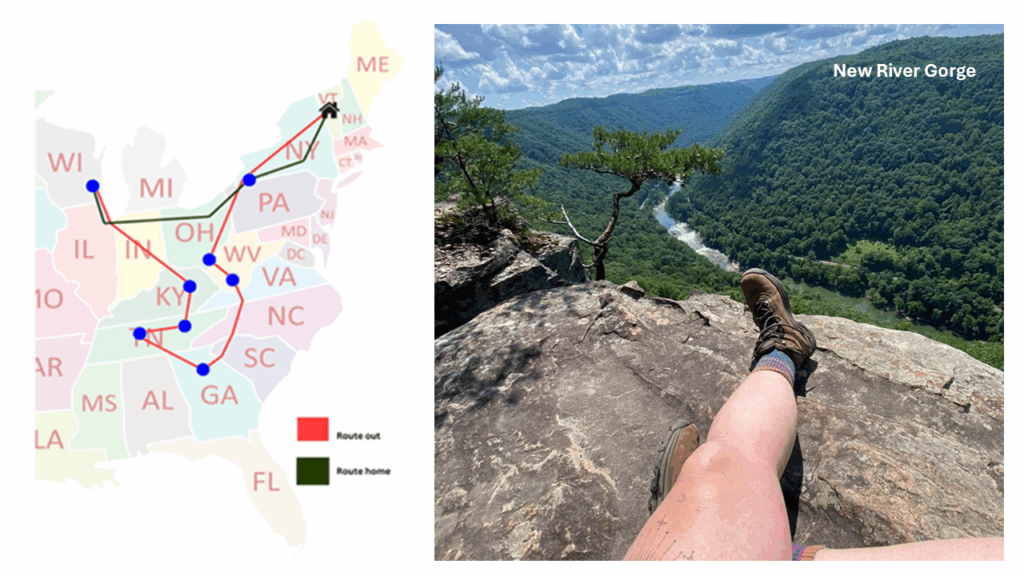

In the summer of 2024, I had the big adventure I had always craved and drove around the country for weeks on end. With only a few planned stops, I was mostly free to go where I felt called. I packed up my car with my sleeping bag and tent, cans of beans and pouches of rice, a little pot for boiling water and cooking, my coffee and a French press, and I hit the road. I had a long first day of driving across western New York and northern Ohio, so as one might imagine, starting to see hills again as I reached southern Ohio gave me great relief from driving’s monotony. I decided to stop and see what I could find in the way of a bite to eat and found myself walking through the doors of a local watering hole in Gallipolis, a town on the Ohio river.

At midday, the room was mostly as expected, quiet, with a few guys in their neon roadcrew vests just out of work playing a game of pool. They chatted together and with the bartender in a familiar type of way. You could tell they’d all known each other for a while.

Whether you’re having a glass of ice water or a pint of Guinness, dive bars are the place to go when you are travelling. Sit and listen, talk but do not take up more space than necessary, learn what there is to be shared. The person sitting on the stool next to you has the potential to become a friend or a lesson. The magic of travel happens in places like this.

The bartender and I talked for a good few hours. She asked where I was from, and between bites of my burger and sips of my drink, I told her of my home and she told me of hers. I felt ignorant for it, but I wasn’t expecting much in the way of a country accent while still in the state of Ohio but sure enough I was hearing it. I felt silly afterwards for expecting a state border to drastically change the folks on either side of it. She was friendly but had a sort of “no-nonsense” demeanor I recognized from some of the women in my own life. When you’re busy taking care of your house, working full time, and carrying the emotional load of family, you don’t have time to mince words. We bonded over some shared experiences, having both been raised in the country: we laughed about 45-minute bus rides to school and having to go sometimes more than one town over for the grocery store.

I laid some cash down on the bar to settle up; she gave me a sticker from the bar and wished me luck on my trip as we parted ways.

West Virginia and her steep mountains quickly came up all around me and I was in awe. The hills all seemed much steeper than back home. I knew immediately I wanted to stop and stay here a while. I pitched a tent in the New River Gorge area, cooked a can of beans, ate a quick dinner, and made my way to town. When I entered the nearest bar I could find in Fayetteville, the only other soul in the room was an orange cat napping on one of the barstools. I bent down to scratch behind his ear and said aloud, “Who are you?”

“That’s the owner,” said a deadpan voice as a man came through the back door and made his way to a seat at the bar, smelling of a freshly smoked cigarette. I chuckled and settled onto a stool myself. About five seconds later, four or five more people, all laughing and chiding, spilled in through the back door in that same haze of nicotine. A man who had just come in with the group introduced himself and asked my name. Immediately after, he asked me where I was from. I laughed and replied, “That obvious I’m from out of town?” He nodded and chuckled.

Most of the people at the bar that night worked in the tourist industry, a familiar story from my life back home. Vermont has many wealthy visitors to the state each year, mostly to enjoy our mountains and ski at the resorts. Much of their money, however, does not stay there for the benefit of the Vermont people. It goes to the big cities and to the men in suits behind desks. Vail, a multibillion-dollar company, owns the mountain resorts back home, and they would step on anyone in their way.

In the words of Vermont songwriter Noah Kahan, “This place had a heartbeat in its day // Vail bought the mountains, and nothing was the same.”

Since I was 15 years old, I have worked in restaurants and primarily those that cater to tourists. If you need a job back home, that’s where they mostly are.

In this shared truth, I bonded with the folks I met that night. We swapped war stories of the worst of the worst in tourist behavior. We lamented over how it felt like most of these rich folks left a place worse than they found it.

Throughout the night more people came to the little bar, usually being met with a burst of greetings and conversation from the group. Throughout the night I was added as a friend on social media, invited to see some music the next day, and to go on a kayaking tour by different people, all outgoing, friendly and seemingly eager to make my acquaintance. This embrace was in stark contrast to my experiences back home. People from Vermont are kind. They will give you the shirt off their back if you need it, but it’ll come with some wry wittisms. We also tend toward the shy side, and I wonder if it’s the generations of bitter cold that have made us quiet.

In the little bar that night, we laughed, and we drank, and when the night was over and I lay down in my tent, I realized I needed to stay for at least a week to see some music, explore, and hang out with some new buddies.

***

Leaving West Virginia, I hit I77 to I81 south then I26 east at Johnson city, and I20 to Augusta. I generally avoid tolls which leads me to countless more turns and smaller highways, but I found my way down to Atlanta . After a week with friends, I spent some time in Nashville, Knoxville, and some driving through the Smokies, trying to keep my eyes on the road instead of staring at the mountains. I next found myself in Kentucky for about two weeks, camping out in Beattyville in Lee County. I drove the back roads, seeing dogs and kids running free through the grass and people sitting on their front porches, and I thought of how this could be Vermont, of how two mountain communities with almost a thousand miles between could look and feel so similar. I thought of how weeks on the road and loneliness could be soothed by just being in a place that looked like home. The mountains are a salve to me.

Before leaving Kentucky, I stopped in Berea, a place I had heard about and walked into the Loyal Jones Appalachian Center. While reading some poetry displayed in the hall gallery, Chris Green (the center’s director) walked by and started talking to me about writing and poetry. I told him about my own poetry, and he told me about magazines where you can submit your writing. We talked about sense of place and the similarities I’d so far experienced on my trip. It was one of those conversations that truly fills your cup. I left feeling recharged and excited about all there is to learn and do and see.

I marveled at the big cities along the way and was taken in by the countless microcosms of diverse communities. I love some cities dearly and always will, but there’s nothing that beats the feeling of home and the familial feeling of being in a mountainous country place.

I think I can see a mother in the Mountains, her face green and textured by leaves high above all else. As I got closer to home, I felt her looking at me. I know this land, and it knows me. My flesh, bone, and organs must be comprised of Vermont now, as surely at 10 generations in, you must share a connection with the place your predecessors lived and died and everything in between. The trees and hills here have witnessed the cruelty and joys of life upon one family over many, many years. Did they feel sadness when my great grandmother's baby boy succumbed to meningitis? When his little eyes filled with tears as his father held him down and the doctor gave him those shots, did they feel the sharp pain with him? A full human life is nothing to that of a tree, and even less to the mountains, just a blip. So a life made up of only four years? What was that in the grand scheme of things? When his mother grieved the loss of a child but carried on anyhow (what else was she supposed to do?) did they feel that hollow ache radiating from that rail-side cabin out? Did they care?

I can’t sleep in a flat place.

Back home again, I found a beauty in the weeds that crop up on the shoulder of the gravel roads. A blanketing of coltsfoot forms the backdrop to wild carrot and black-eyed susan's. Cat grass sways in the wind and goldenrod stands tall. There is yarrow speckled amongst the hundreds of sweet purple clovers. If you walk down to the river, you can fashion a humble, wildflower bouquet along the way and tie it together with a blade of long grass. You can toss it in the water and watch the colors float downstream and away.

In the farthest corner of my family home, behind the garden and the barn, stands a grove of quaking aspens. Their soft rattle is a lullaby to me. A few weeks after returning home, I began putting together my application for Berea College.

I had the big adventure I had always craved, drove around the country for weeks on end and came back to the arms of Vermont, loving her more than ever, but also carrying with me the love of other places’ kindred spirit.